Over the past two years, there has been an explosion in the amount of artificial intelligence (AI) software available, not just to healthcare professionals like myself, but to the general public. In many ways, AI has been quite helpful. I myself have been using AI scribe software in my office for close to a year now. The software listens to the conversation I have with my patient, and automatically generates a clinical note.

The AI scribe has been an enormous benefit to me. My medical notes are much better (also somewhat more detailed). I also save one hour of admin time a day (!) As an aside, this is actually a reason why the government should fund AI scribes for physicians. Under the new FHO+ model, we are paid an hourly rate for administrative work. Surely, saving five hours of physicians time a week is worth the government purchasing a scribe for physicians.

There are also some significant benefits for patient care. Another piece of AI software I use (that’s restricted to health care professionals) helps me with challenging cases. I am able to put the symptoms and test results into the software and it generates a list of potential diagnoses, and suggestions for next steps. It can also recommend treatments for rare conditions.

The general public can also benefit from AI. I recently had a little bit of trouble with my trusty 13-year-old SUV. I put the make and model of the SUV into a commercially available AI, put the symptoms in, and it generated a list of potential causes based on known issues about my SUV.

To be abundantly clear, I would never attempt to fix a car myself. Just as, with all due respect, patients should never, ever attempt to implement a treatment plan for themselves. What AI did do is give me the ability to have an intelligent conversation with the auto mechanic about the situation. And, dare I say it, allowed me to ensure that the mechanic was not trying to pull the wool over my eyes. (My vehicle is now fixed and running very smoothly.)

But along with the many benefits of AI software, there is, of course, potential for harm. This can range from ludicrous to dangerous.

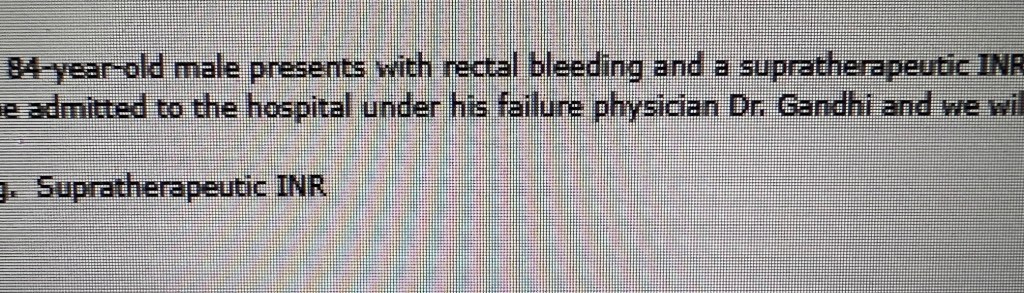

The phenomenon of AI scribe hallucination is well known to physicians like myself. I have seen it in my own software, and it is the reason why I always read the note before I paste it into the patient’s chart. Admittedly, some of that is laughable :

Additionally, the reality is that AI scribes can’t often put a patient’s lived experience (which is so important to building a relationship with a patient) into a note. My colleague Keith Thompson had a superb post on LinkedIn talking about how the AI scribe failed to recognize his personal interactions with an Indigenous patient, particularly with respect to understanding generational trauma.

Sadly, there have been cases where actual harm has been caused by AI. Grok is currently being investigated for generating sexualized images without consent, including those of minors. This causes severe emotional distress and real harm to the victims. There have also been concerns that AI chatbots are helping or suggesting people harm themselves. No one wants any of this stuff to happen, including the people who write AI software. But it has happened.

All of which reminds me of something that my computer science teacher in high school was fond of saying. (Note to my younger readers, and particularly my sons if they ever read my blog: Yes, there actually were computers when I was a teenager. I am not that prehistoric!)

The redoubtable Mr. Williams always implored:

“Do not forget, computers and software are actually very very stupid. They can do some things very fast, but they can only do what they are told.”

It’s a piece of wisdom that still holds true today.

With processing speeds almost infinitely faster than when I took computer science, computers can do multiple calculations very very fast. My desktop computer, which is a few generations old, can run 11 trillion operations a second. Heck my phone, which itself is 4 years old, could probably run a fleet of 1980s Space Shuttles. Speed is not the problem now.

The problem is that these computers and software still don’t actually have the ability to “think” outside of their parameters. They only do what they are programmed to do. If for example, they are programmed to answer questions asked by a user, but they are not given specific rules to avoid illegal answers, well, they will answer the questions directly. If the programming contains an inadvertent error (someone entered a “0” in the code, instead of a “1”), well, then the software will NOT be able to realize that was a mistake, and will carry out calculations based on the wrong code.

It is true that software is increasingly being taught to “look” for errors. But again, the software can only see the errors it is programmed to look for. It can’t find inadvertent errors and it can’t “think outside of the box.” They are, for lack of better wording, too stupid to do so.

All of which is my fancy and longish way of saying that while these new tools are great, at the end of the day they simply cannot replace the human experience. Just as the software couldn’t recognize the generational trauma of an Indigenous patient, there is a lack of “gut instinct” present. That feeling you have when you are missing something, and you know a patient is sicker than they may seem. It’s a trait that seen in our best clinicians, and one that no programming can replace.

Using an AI tool is just fine. But for my part, I’m going to agree with Mr. Spock: