To: Dr. Cathy Faulds, Board Chair, and Ms. Kimberly Moran, CEO, Ontario Medical Association

Dear Dr. Faulds and Ms. Moran,

I’m writing to express my extreme displeasure about how the OMA has handled the elections process. The past couple of years have seen more and more that the OMA, as an organization, has sought to limit the ability of front line members to choose their representatives. This has had the effect of further disenfranchising the hard working physicians whom you are supposed to serve.

In the past couple of years, the OMA as an organization has put in extremely restrictive rules on candidates, particularly for Board Director. Candidates were not allowed to “campaign”. Candidates for Board and President can only offer up a brief statement that answers certain questions, and not much else. Town Halls were controlled with Orwellian like micromanagement. All candidates could only submit a pre-approved list of skills. No one is allowed to let their personality show through.

Even asking candidates a question, like I did last year, is verboten. The penalty for daring to ask candidates to answer a difficult question was to have your career and livelihood threatened by a code of conduct complaint.

This year, the elections process is markedly worse. Instead of letting members choose who they wish, you shortlisted candidates. (NB – please spare me the nonsense about hiring an “independent” third party to review the candidates – we all know that “independent” consultants get guidance from the organization they are hired by. They just do the dirty work of the hiring organization).

I will NEVER criticize a candidate for running (I may criticize their position or views – but not for choosing to run). It takes a lot of guts to stand up and bear the slings and arrows that inevitably come your way. BUT, the blunt reality is that your “shortlisting” process is by default going to create an entirely bland, non-confrontational and non-outspoken Board. It will create a Board that will not provide appropriate oversight to the OMA.

For example, one of your approved Board candidates was asked on Social Media if elected they would commit to change the direction of the OMA so that it would stop speaking out against expanding the scope of practice for pharmacists and others. (The questioner has been very vocal that allied health care providers can do much more). Your approved candidate replied with a response (I’m paraphrasing):

“I will always be on TeamPatient. We need to follow the evidence where it leads.”

The questioner was quite happy and obviously didn’t realize that the exact same response could be given if someone had asked the candidate: “Will you get the OMA to be MORE forceful in preventing expansion of scope of practice to allied health care professionals.” It’s the type of bland, non-specific, non-controversial response that is often taught in various “Leadership” courses and “Director” courses. You know, the type that is designed first and foremost to not offend anyone, while making everyone on both sides think you agree with them in the hopes that this will somehow make you able to enact change.

(I’m not naming the candidate because truth be told, overall I actually like the person and if it wasn’t for the shenanigans that the OMA has been doing, would likely have voted for them – It was just too good an example to illustrate my point to pass up).

What’s worse is how you have treated the current list of candidates for President Elect. While I absolutely would agree with doing a social media search (along with other reasonable background searches for a position of such importance) – the decision should simply have been one of if a candidate is appropriate or not. And if not – they should not be allowed to run, and the OMA should deal with the consequences.

Instead, the OMA, under your leadership, has chosen to promote a document that characterizes one of the P/E candidates in a negative manner. (Yes this was the third party view – but you already know what I think of third party views). This negative characterization can, and should, open you up to legal action (whose defence will be paid for by my dues – which I find even more objectionable). Attaching subjective comments to the profiles of eligible candidates is outside of established governance norms.

ALL of these actions smack of the OMA as an organization self selecting candidates that the OMA finds suitable (not the members). It reeks of the organization wanting a complacent Board, a Board that simply rubber stamps what “experts” bring in front of it, rather than a Board that provides true oversight. True oversight demands that the Board ask hard, uncompromising and uncomfortable questions of the staff when appropriate. I can’t see a thing in your Board vetting process that would suggest you let candidates with these skills through.

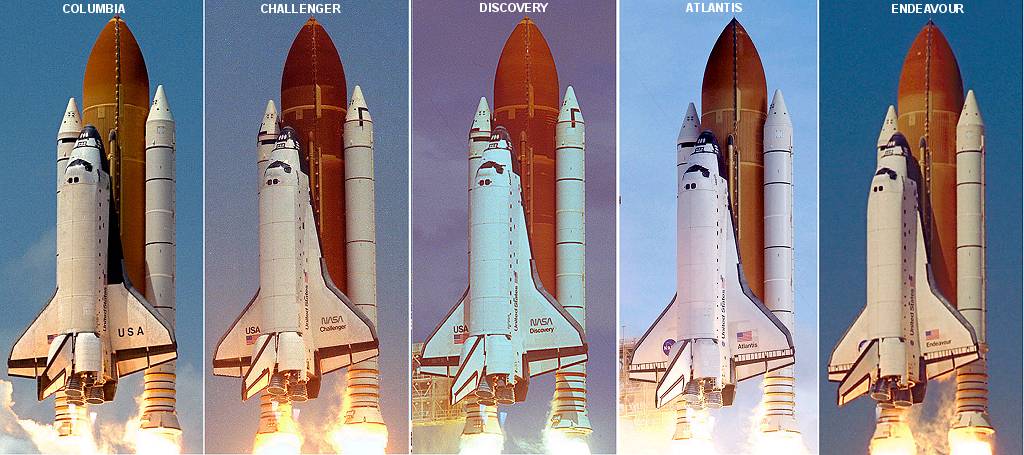

You are undoubtedly aware that as a result of the actions of your current leadership, both Dr. Paul Hacker and Dr. Paul Conte have publicly resigned as Board Directors. Historically, the last Board Director that resigned under similar tumult was Dr. Shawn Whatley in 2016 . That was the same time as the disastrous tPSA fiasco. He was one of 25 (ish) physicians, or 4% of the physician Board Directors. You’ve lost two of 8 physicians – or 25%. That’s a critical blow. (Dr. Alam resigned a month early as well – but that was with much less fanfare).

What’s worse is the calibre of Directors that resigned. Dr. Hacker co-chaired the Governance Transformation committee of the OMA. Dr. Conte not only chaired the Governance and Nominating Committee, but was Board Chair. Having worked with them, I can tell you that both members have extremely high levels of integrity and both are extremely well versed in governance. They are absolute titans of good governance principles. They KNOW when governance is going off the rails, and for them to take this steps speaks volumes about your leadership.

In summary then, it appears the OMA, as an organization, has taken well meaning attempts to reform it, and make it more member responsive, and instead turned it into a way to only allow certain, pre approved members to be in charge. Outspoken, critical voices are not allowed. Strong opinions (however well stated) are unwelcome. Independent thought must give way to complacent behaviour.

All of which is my long way of asking, given that you have undemocratically preselected candidates, and impugned those you find wanting, why should any member bother to vote?

Yours truly,

A very very annoyed Old Country Doctor.