On May 6, as part of a needlessly protracted negotiations process, the Ontario Medical Association (OMA) and the Ministry of Health (MOH) began public arbitration hearings to determine a compensation package for physicians for the fiscal year April 1, 2024 to March 31, 2025. Yes, arbitration has begun AFTER the last contract expired, and physicians will need to be given retroactive pay.

This is happening as part of the Binding Arbitration Framework (BAF) between the OMA and the MOH. When the two sides can’t agree on a compensation package after a defined period of time and negotiations, arbitration is invoked. The expectation is that arbitrator William Kaplan will issue an award sometime in August. It’s possible the two sides may reach an agreement before then as negotiations are allowed to continue during arbitration. It’s not unheard of that arbitration can sometimes pressure two sides to get a deal done before a decision is rendered.

One common misconception I hear from my colleagues is that Mr. Kaplan will have to pick one side or another. That’s not the case. The BAF we have is for something called Binding Interest Arbitration. Mr. Kaplan will likely award something in between.

Public arbitration, is just that. It means that the arbitration briefs submitted by the two sides are public, and the arbitration hearings are public. Which means that physicians across Ontario know exactly what the government thinks they are worth. And that knowledge will demoralize an already disheartened profession.

Having gone through this process as an OMA Board member in the past, let me acknowledge a few things right off the bat.

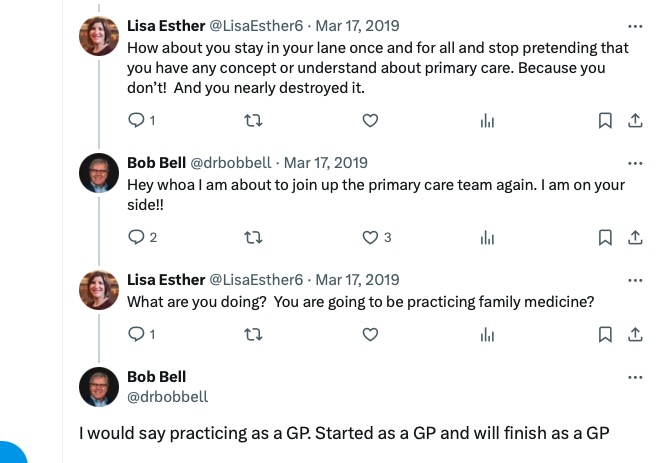

- Arbitration is still a lot better than the alternative, which would be unilateral government action. We’ve been down that road before during the Hoskins/Bell years and that was just plain awful for not just physicians, but patients as well.

- As part of the arbitration process, the government purposefully put a “lowball offer” forward. Basically they know the arbitrator will likely award more than they offer so of course they try to present a lower version than they normally would expect.

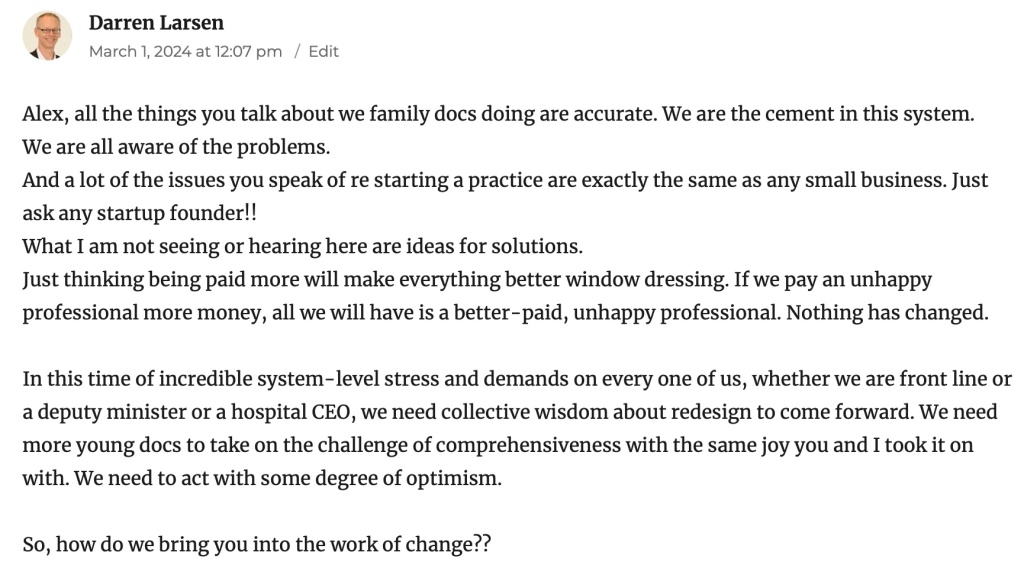

- In that vein, I would have expected the OMA to present a higher request. All physicians deserve a raise, and their proposal does address that. But the ask frankly just catches up (barely) for the last few years so calling their brief a “strong” demand is inaccurate.

- Our negotiations counsel, Messrs Goldblatt and Barrett, frequently told me that it is much better to have a negotiated settlement that both sides agree to, than one that was forced on them by an impartial third party. More chance of the two sides willingly implementing the many nuances in an agreement as complex as the physicians one.

However there is one thing that hasn’t been considered. Arbitration frequently leaves bad feelings amongst the two parties. In the sports world for example, one has to look no further than Toronto Maple Leafs goalie Ilya Samsonov. He took the team to arbitration last summer. The team clearly said some negative things about him to justify their offer to him. While the team has not exactly been forthright about what exactly was wrong with him mentally, there can be no doubt that he had a terrible first half of the hockey season. It was so bad he eventually got demoted (on paper) to the farm team – and his play was so bad no other team in the NHL wanted him (ouch).

This is why sports teams try to avoid arbitration – they know that the process can be ugly, and can adversely affect the performance of their top athletes who have to listen to negative things said about them. For teams to succeed, the top athletes have to play their best.

Looking at the situation in Ontario, it’s frankly hard, as a physician, to feel anything but insulted and disrespected by how the MOH negotiations team has acted. It’s bad enough that they appear to have, for the most part, stalled the negotiations to the point where arbitration is needed. Contrast this with Manitoba, Saskatchewan and British Columbia, where the governments realized that they needed to retain their physicians due to the current crisis in health care, and made widely applauded agreements with their doctors. But Ontario’s arbitration position is so pathetically inadequate (even when considering they are low balling for arbitration) that one really has to wonder if they want to have good relationships with their doctors going forward.

From 2020 to 2023 – inflation has gone up by 14.8% (with another 2.9% for this year so far). Nurses were given an additional 6.75% (on top of their previous agreements) due to the unconstitutionality of Bill 124. And yet the MOH thinks physicians should only get three percent?? With no recognition of administrative burden? And the MOH claims there are no retention/recruitment issues?? Have they talked to the over 2 million people without a family doctor??

Does their negotiations team truly understand the harm they are doing by putting forward such an insulting and offensive proposal??

Here’s the thing, after a contract is agreed to or arbitrated, physicians and government will need to work together for the benefit of the people of Ontario. Yet how does any reasonable person expect physicians to work with a government team that on the one hand says that “physicians are valued and respected” but then, at the first chance they get, demean them with such a pathetic position.

Remember, many of the bureaucrats who provide supporting information to the MOH’s negotiations team have other roles. They’ll show up on other bilateral committees between physicians and the MOH. And after you denigrate people so badly with such an abhorrent brief, will there really be any trust between the two sides (and yes, they are now sides – this opening position makes it clear we are not on the same “team”).

Just like the Leafs needed Samsonov to, you know, make a few saves earlier in the season, the government needs physicians at their peak to deal with and give their best advice on the current mess that is health care. And while physicians, as is their nature, will genuinely try their hardest to do so – the blunt reality is that Samsonov tried his best to make more saves as well. But when your head is not in the right space……..

At this point there really is only one solution. The MOH negotiations team needs to formally apologize to all physicians for their incredibly repulsive offer. Then they need to look at BC, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, and put together a fair and competitive agreement so that more physicians don’t look elsewhere. This can be done tomorrow.

Otherwise, I genuinely fear that we are going to continue to lose physicians, not only in fields where they are desperately needed, but to other jurisdictions as well.