My thanks to Dr. Ramsey Hijazi, founder of the OUFP, and one of the strongest advocates for improving family medicine that I know, for guest blogging for me today. Unfortunately, the government didn’t listen to Dr. Hijazi, and as a result he left family practice earlier this year. In this blog he reflects on how his life has changed since.

It was a busy Saturday morning at my daughter’s dance competition in April 2024. The family had all got up at 5am to get ready for the day. The morning was hectic getting the kids and dog dressed and fed, making sure we didn’t forget supplies for the day, packing snacks and then rushing across the city to Hull for the competition.

My wife helped bring my daughter and her sister backstage to get dressed and prepare for practice. I watched my 2 year old son run tirelessly down the hall of the venue screaming in pleasure. I watched with a sense of calm and patience that I hadn’t felt in a very long time. More than I can remember I felt….present. The previous day I had left my family practice to pursue a position as a hospitalist. In less than 24 hours (and to my own disbelief) I noticed a distinct difference in my frame of mind.

Leaving family practice was not an easy decision. It is a rewarding and challenging career where you can make a positive difference in the lives of your patients. You get to know your patients better than anyone else in the medical system as you care for them from birth to old age. Their journeys in the medical system can remain with you forever. I became a family doctor because I loved family medicine and I am grateful for having had the opportunity to practice and take care of my patients. It is also part of the reason I started the Ontario Union of Family Physicians in July 2023 to help advocate for changes to improve the working conditions of family doctors. I had hoped to continue this work.

However, over the last several years the landscape of family practice has deteriorated significantly. The administrative or paperwork burden in family medicine has ballooned to almost 20 hrs/week. It is a constant barrage of work that is being downloaded or dumped on to family doctors from specialists, insurance companies and pharmacies. There’s also the extraordinary duplication of lengthy and sometimes irrelevant hospital reports that come in daily for review.

In essence, you supervise every single step all of your patients take in the medical system whether you have seen them recently or not. You ensure that tests and follow ups are completed and that nothing falls through the cracks. If my patients did not have me overseeing their journey in the system, countless tests and follow ups would get missed and never take place.

Like it or not, family physicians have been unofficially assigned the responsibility to make sure things actually get done when no one else will. It is mentally exhausting. There were days I would come home from work feeling so overstimulated I could do nothing more than sit on the couch and keep silently to myself for the rest of the night (although young kids make that a difficult reality to realize).

In an age where patients can simply email their family doctor you are never unplugged from your job. Despite trying to convince myself that I wouldn’t think or worry about work on vacation, I couldn’t help but have intrusive thoughts that occupied my mind. I would drift away from the present moment I was trying to enjoy. Often I would use the first and last days of my vacation as a desperate attempt to try and be caught up.

On weekends when not much was happening, such as watching TV with the kids or supervising them in the backyard I also couldn’t help but have the same intrusive thoughts of thinking my time could be better spent trying to catch up on the paperwork that was piling in. I very much resented having these thoughts.

Now add this to the stress of running a family practice. Business expenses have steadily increased with a dramatic spike in the last 3-4 years without any real increase in OHIP revenue. Running a business can be a stressful, but worthwhile endeavour. Unfortunately, this couldn’t be further from the reality of running a family practice. Revenue from OHIP continues to pay less year over year relative to inflation and expenses.

The OMA has kept track of OHIP rates relative to inflation to show current rates are only 37% of what OHIP used to pay physicians to run their practice. For the newer family doctors entering practice the future stability of the profession is truly grim. They enter practice with huge loads of debt and an almost guarantee they will take home less and less money every year despite the workload contrarily increasing year over year. With no pension, benefits, paid sick time or vacation to top it off, the reality for recent grads is that without significant changes to help the profession, it is no longer a viable career option.

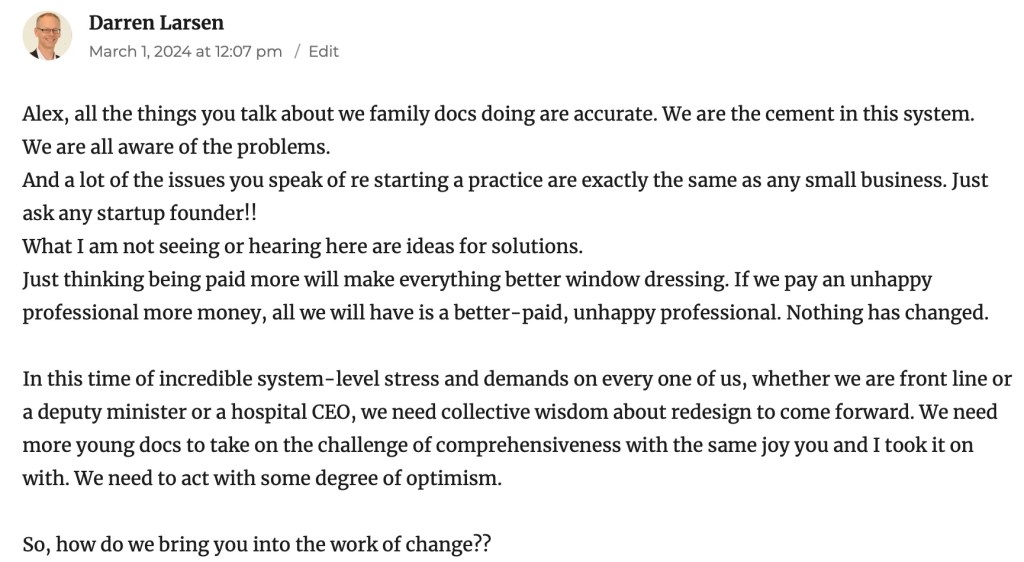

Many family doctors work side jobs to help financially subsidize their practice. Granted, the entire medical system is plagued with poor working conditions, underfunding and increasing burdens of work, however, the situation is particularly magnified in family medicine. But you don’t need to take my word for it, just look around to see what is going on in your community and in our province. Despite the OMA showing statistics that we have more doctors trained in family medicine per capita than ever before, we are in one of the worst shortages ever.

Family doctors simply don’t want to do family medicine any more.

Changing my career path to work in the hospital as a hospitalist was a big risk and required a leap of faith (I hadn’t worked in a hospital since I finished residency). But unfortunately, in family medicine I had become increasingly unhappy professionally and personally. As it turns out, becoming a hospitalist was the best decision I could have ever made. Working in hospital means I am responsible only for the patients on my ward and not 1500 patients in the medical system. I must round on and see each patient to review their medical problems, perform examinations and order any tests or investigations. I follow up with family when needed and appropriate for medical updates. At the end of the day unless I am on call, I walk through the door to go home and my work is done until I arrive again the next morning. There is no appointment schedule to rigidly follow and I can take as much or as little time that is needed for each patient. If something unexpected occurs, I can deal with it and get back to my work without the worry or stress of being behind schedule and having irritated patients. It is also challenging and extremely rewarding.

No longer do I have all the stresses of running a business or see up to 40% of my OHIP billings go towards business expenses. No longer do I need to reconcile rushing several patients in and out of the clinic for appointments to stay on schedule and maintain a reasonable availability while also trying to give the appropriate time to address their concerns. No longer do I leave work at the end of the day, eat dinner with the family and go back to the computer to tackle the never ending pile of paperwork. No longer do I need to worry and stress while on vacation about all the work that is piling up in my absence. No longer do I have the intrusive thoughts of working on paperwork while watching the kids ride their bikes or to watch my son run down that venue hall aimlessly in pleasure.

I am more present and at peace. I am a better person, husband and parent because of my decision to leave family practice and that is perhaps the saddest and scariest thing about this entire journey.