Recently, I attended the Menopause Society’s Biennial National Scientific Conference. I’ve long felt that medicine as a whole has done a poor job on women’s health issues, and wanted to learn more about what I can do to better help my patients. The conference itself was packed (over 600 attendees). Half of them were family doctors like myself. As with all medical conferences, not only did I get the chance to learn some valuable information to benefit my patients, I got a chance to network with colleagues from across the country.

Sadly however, a rather large number of family doctors I met were in a similar state of mind. They were tired, burnt out, and were actively exploring ways to stop practicing family medicine. In short, they were all giving up.

A dear friend of mine is taking 6 months off her practice to re-evaluate her work (despite having helped countless numbers of people over the years). Another physician has found happiness working part time at a specialty clinic and occasionally doing locums (vacation relief work). Another is actively looking to find someone to take over his practice. Another is simply going to close her practice after two years of trying to find someone to take over. Another…….ah, you get the point.

About one -third of the family doctors I spoke to were all at some stage of quitting family medicine. Given that Canada has 6 million people without a family doctor – which is already a disaster- it’s safe to say our health care system won’t survive if this happens.

About the only part of the country where family doctors seemed to want to carry on was Manitoba. They cited a new contract that fairly compensated them for their work, and a reasonably positive working relationship with the government. I guess that’s why Manitoba set a new record for recruiting physicians last year. Paying people fairly and working with them co-operatively will attract new talent? Who knew?

(As an aside, Manitoba is also the only province I am aware of that has a specific billing code for counselling women on issues related to peri-menopause and menopause).

But I digress. The question becomes why are so many family doctors planning on giving up? I would suggest it’s a host of issues. There is an increasing level of burnout in the profession. It’s primarily driven by by the administrative workload which has gotten out of hand. For example, I recently went on vacation to Manitoulin Island, and while waiting for the ferry, I couldn’t help but pull out my laptop and check my lab work and messages. I knew that if I didn’t check my labs every day, the workload on my first day back would be crushing.

There’s also the constant delays in getting patients tests and referrals to specialists. The most common message I get from my patients is something along the lines of “I haven’t heard from the specialist/diagnostic test people yet, do you know when it’s going to be?”

And of course there is the ever present “But my naturopath told me you could order my serum rhubarb levels for free” and “I did a search online and it told me I need a full body MRI”.

The worst part of it of course, is that the family doctor becomes the brunt of the frustration and anger that patients express when the health care system doesn’t live up to their expectations. I had to tell three patients (while I was on vacation) that, no, I couldn’t do anything to speed up the specialist appointment. Four more were told that I had in fact called the pharmacy with their prescriptions – and I had the fax logs/email logs to prove it. And so on…

So what can be done?

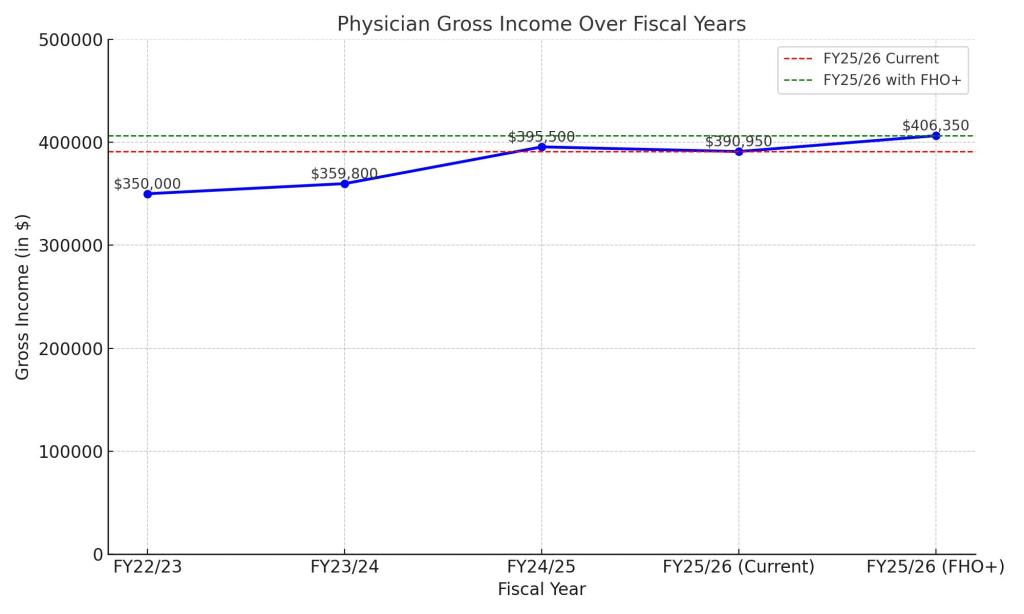

In the absence of anything else of course, the first thing is to pay family doctors more. Recently, the Ontario Medical Association (OMA) and the Ministry of Health (MoH) have rolled out the “FHO+” model of paying physicians. There is a slight bump in pay (about 4% for the next fiscal year over this year). There is also an acknowledgement that administrative work needs to get paid and some other tweaks. It’s perhaps a start, but in the current system, a 4% raise will not stop the haemorrhaging of family physicians.

What really needs to happen is for Ontario to forcibly, quickly and rapidly move to a modernized, province wide electronic medical records system. I’ve been talking about this for years and years and even presented on this to eHealth Ontario (in 2018!). But I have not been able to explain it as well as my colleague Dr. Iris Gorfinkel did in her recent Toronto Star Op-ed. (It’s a really good read and I encourage you all to read it). To shamelessly quote her:

“A fully integrated, province‑wide, patient‑accessible electronic health record system should no longer be viewed as a luxury, but an essential part of the solution to Ontario’s existing crisis…… It would free family doctors to do the work only we can do.”

Secondly, we need to rapidly move towards team based care with family physicians as the lead of the team. While the MoH is announcing teams proudly in the hopes of connecting patients with doctors, the rollout seems kind of uneven. They amount to a call for proposals as opposed to a specific evidence based structure of how these teams should run. There’s also no specific role guarantees for family physicians in these teams (beyond saying they are important). The process seems slipshod at best.

Finally, at the end of the day we must not shame or diminish those family physicians who have given up. Many of them have spent years, if not decades fighting for better care for their patients. The fact that the unrelenting bureaucracy of our cumbersome health care system finally got to them and made them give up should be cause to shame the people in charge of health care, not the individual physicians.

Let’s hope that message gets across.