My thanks to Dr. Mike Goodwin (pictured inset) for guest blogging for me today. Dr. Goodwin is a retired family physician who held numerous roles in medical politics including (but not limited to) being a member of the Coalition of Family Physicians, a member of the Section of General and Family Practice Executive and an OMA Board Director. He brings a historical perspective regarding medical audits to this blog, and I am grateful for his contribution.

I admire our courageous young colleague Dr. Elaine Ma, she of the seemingly never-ending OHIP billing/auditing dispute with a media savvy beyond her years. Dr. Ma’s impeccable sense of public health propriety during COVID has earned her a growing band of supporters. It has hopefully gained her financial support from both the Ontario Medical Association (OMA) and the Canadian Medical Protective Association.

But what Dr. Ma and younger colleagues may not appreciate is that OHIP’s abuse of doctors, utilizing its antiquated billing payment and auditing processes, has been ongoing for a long time. Between the years 2000 through 2005, a hundred odd doctors every year in Ontario were being subjected to the same sort of unfair retroactive audit, which Dr. Ma is currently experiencing.

Back then, just like now, we had a Schedule of Benefits (SOB) badly in need of an update, a pettifogging bureaucracy unwilling to interpret said schedule with any modicum of common sense… vague auditing rules which conferred the burden of proof upon the accused rather than the province, and the same one-sided authority to claw back payments or garnish future accounts receivable. OHIP even had computers back then, almost certainly the same ancient models they still use today (which they claim can’t possibly be configured to pay doctors in a timely manner after the award of binding arbitrated pay increases).

Administrative abuse of the profession in the very early aughts was rampant. OHIP had enlisted the help of the CPSO, because the College had administrative and regulatory authority, beyond criminal law, over all physicians pertaining to the practice of medicine. Actual auditing and enforcement of decisions was done by an entity of the College called the Medical Review Committee (MRC). It apparently escaped everyone’s notice at the time, and still today, that medical billing to OHIP was and is based upon definitions contained within an official MOH document called the OHIP SOB. The OHIP SOB is, at least in theory, derived from agreements negotiated between the province and the OMA, not the College! One might argue, logically, that any dispute concerning rules and definitions documented within the SOB should always be addressed in the first instance between the Ministry and the OMA.

At any rate, anger and despair over the medical billing and auditing system in that far away time came to a head when a gentle Welland paediatrician, Dr. Tony Hsu, committed suicide. I suspect that Tony felt he had lost face by going public with his own particular auditing horror story. The concept of “face” is important in the Chinese diaspora, and Tony, who worked a one in three (sometimes one in two) on call rota at the Welland County General Hospital (without any on-call stipends in those days), in addition to maintaining a community practice, was forced to repay $96,000. He had to take that out of his retirement savings.

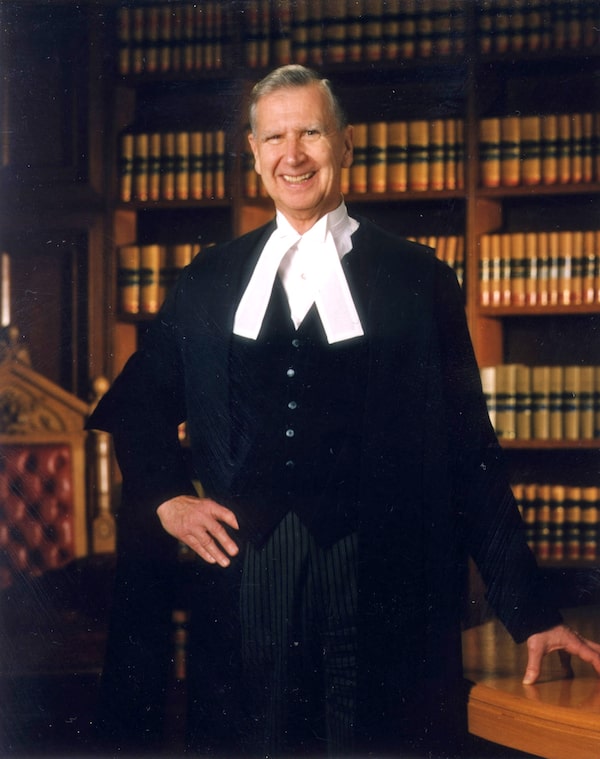

Public and political outrage at Tony’s death, particularly in the Niagara region, was immediate and intense. Then Health Minister George Smitherman was pressed to call for a “public inquiry” into medical billing and auditing. By happy accident, retired Supreme Court Justice Peter Cory was available and appointed to the task. Those of us acquainted with Mr. Cory’s reputation silently cheered.

And when Cory’s very comprehensive report was published, nine months later in April 2005, the indecent OHIP billing auditing system finally came to an end.

Or so we thought!

In his report “Study, Conclusions, and Recommendations Into Medical Audit Practice in Ontario,” Mr. Cory did not mince words. “The medical audit system in Ontario has had a debilitating, and in some cases, devastating effect on physicians and their families,” he said. “It has had a negative effect on the delivery of services, and has undermined Ontario’s attractiveness as a place to practice.”

Also, and very pointedly, the honourable Cory recommended the appointment of a new independent audit board, while declining to take up an offer from the College to continue auditing medical billings as they had been doing prior to his inquiry. In all, Justice Cory made 118 separate recommendations, and I reproduce only the first four, below, since they were (possibly) the most important:

- Jurisdiction and structure: the responsibility for conducting the audits of physicians fee claims should be conferred on a new and independent board. See recommendations (1) to (4).

- Purpose of the audit process: The audit process must be employed only for the purpose of determining the appropriateness of physician fee claims. The audit system itself must be accountable. A biennial stakeholders forum should be established to receive reports on the operation of the new audit process and to receive and consider proposals for its improvement. See recommendations (5) to (7).

- A new emphasis on assisting physicians to comply with billing requirements: The primary goals of the new audit system should be (1) education to facilitate compliance with billing requirements, and (2) identification and elimination of false, fraudulent, and egregiously erroneous billing in a fair and effective manner. See recommendations (8) to (9).

- Schedule of benefits: The schedule of benefits must be revised and adapted. It must also be interpreted flexibly so that a physician is not deprived of payment for a service that is medically appropriate and that complies substantially with the requirements of the fee code. See recommendations (10) to (14).

(NB – as the report cannot be found online, Dr. Goodwin used his own personal copy of the report as a reference – Old Country Doctor)

In the wake of the Cory report, Minister Smitherman ceased audits immediately and promised changes. But no one at the MOH or College lost a job. And ministries or bureaucracies (like the CPSO) are resistant to any change from age-old ways of doing things. That’s particularly true when change might reduce influence, or even more important, authority and funding.

So when I joined the OMA board in 2005 as a newbie director, the ministry was already flooding the zone, as they did, with multiple new issues demanding our attention. Promises made didn’t materialize, and almost none of Mr. Cory’s recommendations, especially the most important, to “confer responsibility for conducting billing audits on a new and independent board,” were implemented. Months became years, and “the Cory report” gradually disappeared from sight, consigned to death by inattention. You can’t find it anywhere today, even with a Google search. Not even on the OMA website: for shame!

I’m convinced that if a significant part of Mr. Cory’s report had been adopted in 2005, much of the shoddy bureaucratic shenanigans from OHIP would have been fixed (including, maybe even their ancient computers). Dr. Elaine Ma would not be undergoing her current marathon persecution. Nor would we be seeing those cases where OHIP seems to let grifters get away with corrupt billing over multiple years before it (OHIP) picks up on the scam. How does that work, by the way?

It’s not every day you get support from a retired Supreme Court justice at your back… particularly such clear, sensible, workable recommendations from arguably the most influential liberal justice of the post-constitutional era in Canada. Peter Cory was famous for his kindness, and for his defence of human dignity at every opportunity…though he definitely had an iron fist in a velvet glove when the need arose. For anyone (like me) who ever had the good fortune to meet him, he was just an unforgettably decent man.

Memo to the OMA:

If you really want to fix this auditing problem, something which I and my colleagues failed to do, Peter Cory’s report from 2005 would still be a great place to start. Dr. Elaine Ma has provided you a good crisis: let’s not waste it.