This blog has been updated to reflect that the fact that the offer from the federal government has been accepted by the provinces.

Lots of chatter about what is an agreed upon funding formula for Health Care between the provinces and the federal government. Some astronomical dollars are being thrown around and called investments in health care. But at the end of the day, will this deal mean better health care for Canadians? The sad answer, is likely no.

One of the advantages(?) of being old is that you’ve lived through lots of things, and can see the past repeating itself. Case in point, in 2004 then Prime Minister Paul Martin introduced a health care “accord” that was designed to “fix health care for a generation“. Essentially the federal government ponied up an eye watering amount of money then, and the provinces were to implement targeted programs that would:

- Reduce wait times

- reform Primary Care

- Develop a National Home Care program

- Provide a National Prescription Drug Program (by 2006!)

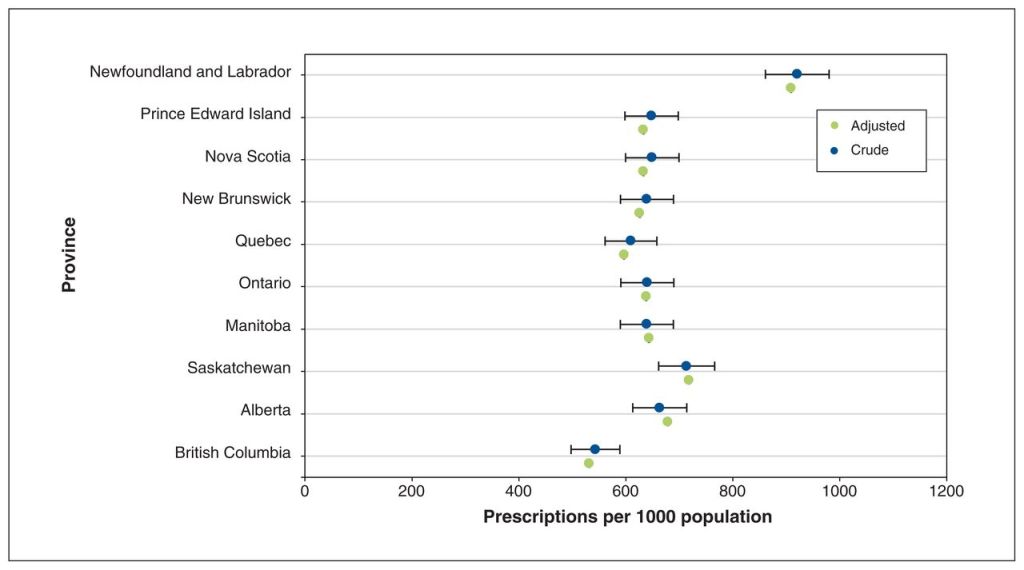

Now Primary Care reform did happen in Ontario, with the development of capitation based payments to family physicians. Think of it as a salary with performance bonuses and you get the gist. There was also the implementation of some Family Health Teams. I’m unaware if any of these were implemented in other Provinces. I do note with interest that British Columbia is only now getting around to reforming primary care with their own new payment model for family physicians.

But both of these programs in Ontario were summarily slashed by then Health Minister Eric Hoskins and his servile deputy Health Minister Dr. Bob Bell in 2015. Indeed their unilateral freezing of the capitation model significantly damaged primary care in Ontario, and the effects of their folly are still being badly felt today by the 2 million residents of Ontario without a family doctor.

OMA Board Vice Chair Audrey Karlinsky put it best on Twitter.

Wait times for surgical procedures however, continued to rise, and I have no idea whatever happened to the National Home Care program.

For those of you paying close attention, the same Eric Hoskins who stopped Primary Care reform in Ontario, went on chair a federal advisory council with the goal of creating a National Prescription Drug Program……….in 2018. Which hasn’t been implemented yet. I suppose being 17 years overdue is not bad by government standards.

By the way, this whole process is basically recycling a failed politician to recycle a failed government promise. And politicians seriously wonder why average Canadians like me are so cynical??

So now, 19 years later, Canadians are being told that the provinces have accepted a federal government proposal to put an eye watering $196 billion into health care, according to Prime Minister Trudeau. But wait they were committed to $150 billion anyway so it’s really only $46 billion more, but wait, when you take out the planned budgeted increases it’s only $21 billion more. Whatever.

In return, for however much money it really is, Trudeau promises there will be “tailored bilateral agreements to address“:

- Family Health Services

- Health workers and the backlog of health care

- Mental health and substance abuse

- Modernized health care system

Our politicians need to study Albert Einstein a bit more.

Here’s the sad truth about our health care system that no politician, of any political stripe seems to be willing to admit. The system is dying and in need of radical surgery. It needs a bold, transformative vision that will completely change the way we deliver health care and will leverage technology appropriately. Anything less is simply more of the same, and will not stave off the inevitable collapse of the system.

How then do we achieve this transformation that is essential to the well being of Canadians? I will go into some further thoughts about this in future blogs, but first I would implore our political leaders to stop listening to old voices who have been advising for decades (if their advice had been good we wouldn’t be in this mess). It’s time to seek out some newer voices who have bright ideas on how to restructure health care delivery in Canada.

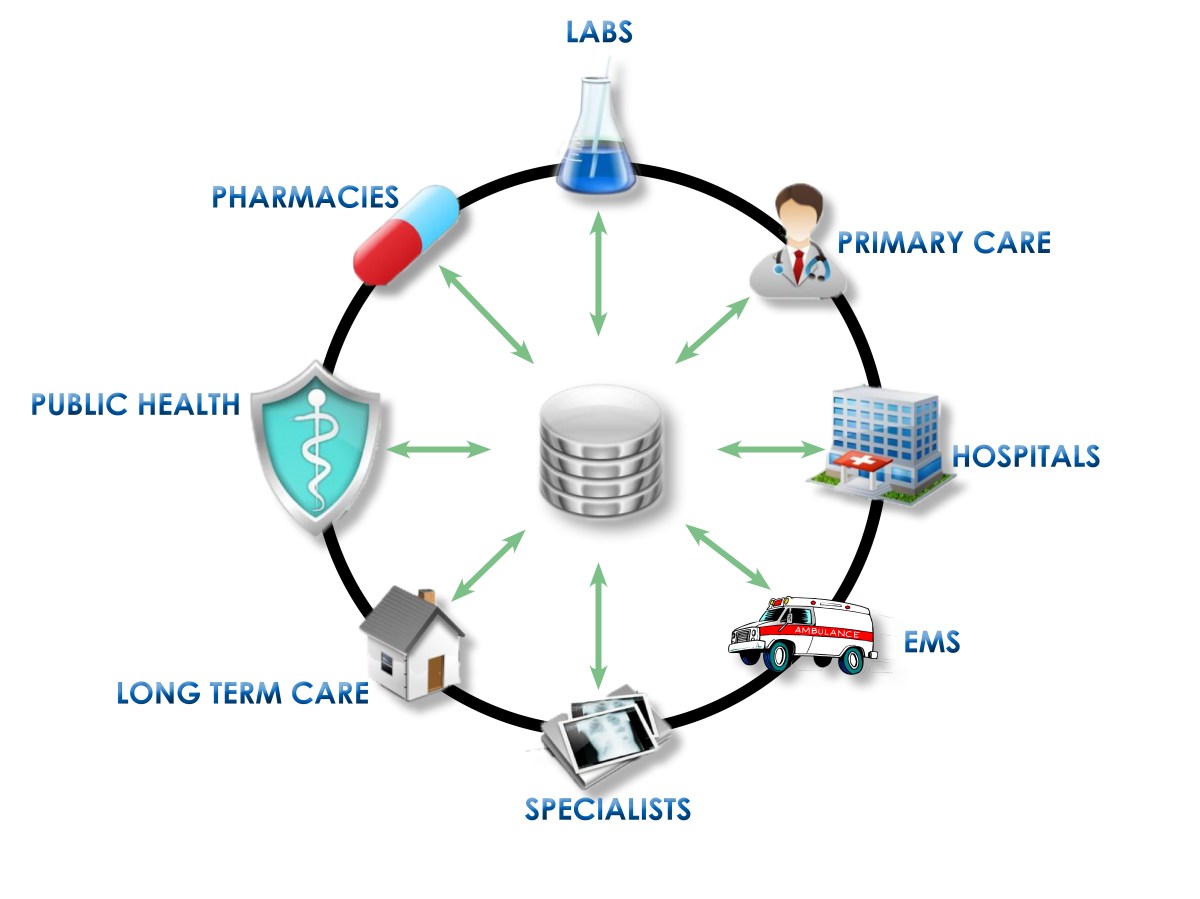

It’s also time to wrest control of health care data management from the current group of bureaucrats in charge of it. We can’t transform health care in Canada without a robust health care IT infrastructure and the current group simply is not getting it done.

As mentioned, I will put some more though into how, in my opinion, health care can be transformed in the future. But for now, just know that whatever the numbers or promises being tossed around, the blunt reality is that it all amounts to trying to spend you way out of trouble.

When has that ever worked out well?